Display Table of Contents

Net-zero homes aim to balance the energy used for heating, hot water and electricity with low-carbon generation, cutting household emissions close to zero. UK housing produces around 20% of national greenhouse gas emissions, mainly from space heating (DESNZ). A net-zero retrofit usually combines insulation upgrades, airtightness improvements and a heat pump, supported by solar PV where suitable. Homeowners should understand costs, disruption, and how changes affect comfort, bills and EPC ratings.

Key takeaways

- Net-zero homes cut operational emissions through fabric efficiency and low-carbon heating.

- Prioritise insulation, airtightness, and ventilation before installing heat pumps or solar.

- Heat pumps work best with low flow temperatures and upgraded radiators or underfloor heating.

- Solar PV and battery storage reduce grid imports, especially with time-of-use tariffs.

- Embodied carbon from materials matters; choose lower-carbon options during renovations.

- Certification and EPC evidence help verify performance and protect resale value.

What ‘net-zero home’ means in the UK: operational carbon, embodied carbon, and boundaries

UK homes produced around 68 million tonnes of CO2e in 2022, equal to about 18% of the UK total (Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, UK greenhouse gas emissions). That scale explains why “net-zero home” claims need clear boundaries. Without agreed definitions, one property can appear “net-zero” by offsetting energy use, while another reaches the same label by cutting demand and electrifying heat.

In the UK context, a net-zero home usually refers to operational carbon: emissions linked to energy used for heating, hot water, lighting, and appliances. Operational carbon depends on both the building and the grid. The UK electricity grid has decarbonised substantially, with carbon intensity falling from roughly 450 gCO2/kWh in 2010 to about 150 gCO2/kWh in 2023 (National Grid ESO, data portal). As a result, switching from a gas boiler to a heat pump can reduce emissions even before insulation upgrades, although the largest savings still come from reducing heat demand.

A robust definition also includes embodied carbon, which covers emissions from manufacturing, transporting, and installing materials, plus maintenance and end-of-life impacts. For new builds, embodied carbon can represent 30–60% of whole-life emissions over a 60-year study period, depending on specification and grid assumptions (Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, RICS). That share rises as operational emissions fall, which makes material choices and refurbishment strategies central to credible net-zero outcomes.

Boundaries determine what counts. Some assessments include only regulated energy (space heating, hot water, fixed lighting), while others also include appliances and cooking. The UK’s official EPC methodology uses the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) and focuses on regulated loads (UK Government, SAP guidance). A homeowner should ask whether a “net-zero” claim covers regulated energy only, whole-home energy, embodied carbon, and whether any residual emissions rely on offsets.

UK policy and standards that shape net-zero homes: Future Homes Standard, Part L, and EPC implications

A homeowner in Manchester replaces a 20-year-old gas boiler with an air-source heat pump and adds loft insulation. When the homeowner applies for a remortgage, the lender requests an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC). The assessor’s recommendations and rating hinge on the building fabric and heating efficiency, not on marketing claims about “net-zero”. A move from EPC band D to C can change borrowing options, because several UK lenders price “green” products around EPC thresholds.

That outcome reflects how policy steers design. The Future Homes Standard sets the direction for new homes, aiming for 75–80% lower operational carbon emissions than current standards (UK Government consultation, 2023). In parallel, Approved Document Part L controls energy efficiency in England through requirements on insulation levels, air tightness and low-carbon heating, with the 2021 uplift tightening performance for new builds.

For existing homes, EPCs translate these technical rules into a consumer-facing signal. EPC ratings run from A to G and use a cost-based model, so electricity prices can affect scores even when a home cuts emissions. As of February 2026, the UK Government’s stated ambition remains for as many homes as possible to reach EPC band C by 2035, with interim milestones shaping retrofit demand and contractor capacity.

Core fabric measures that cut heat demand: insulation levels, airtightness targets, and thermal bridging control

Net-zero retrofits often follow two routes: Option A improves insulation and airtightness to cut heat demand; Option B upgrades low-carbon heating while keeping the fabric closer to standard. Option A usually delivers larger, more predictable savings because space heating uses about 60% of UK household energy (2024, DESNZ: Energy Consumption in the UK). Option B can cut emissions quickly, but higher heat demand can require a larger heat pump and raise running costs.

| Measure | Option A: fabric-led | Option B: services-led |

|---|---|---|

| Insulation levels | Targets low U-values across roof, walls, and floors | Selective upgrades; accepts higher heat loss |

| Airtightness | Sets a tested air leakage target and seals junctions | Basic draught-proofing; limited testing |

| Thermal bridging | Designs out cold bridges at lintels, eaves, and sills | Often unmanaged; higher condensation risk |

Tighter homes need planned ventilation to protect indoor air quality; Building Regulations Approved Document F sets minimum rates. Fabric-first work reduces peak heat load, which can allow smaller radiators and a lower-capacity heat pump, improving seasonal efficiency. Thermal bridge control matters because cold spots can fall below the dew point, increasing mould risk around corners and openings.

Low-carbon heat and power options for homeowners: heat pumps, solar PV, batteries, and smart tariffs

Many UK homes still rely on gas boilers, and space heating remains the largest driver of household energy use. In high-demand properties, electrifying heat can raise peak electricity use and bills, even as emissions fall.

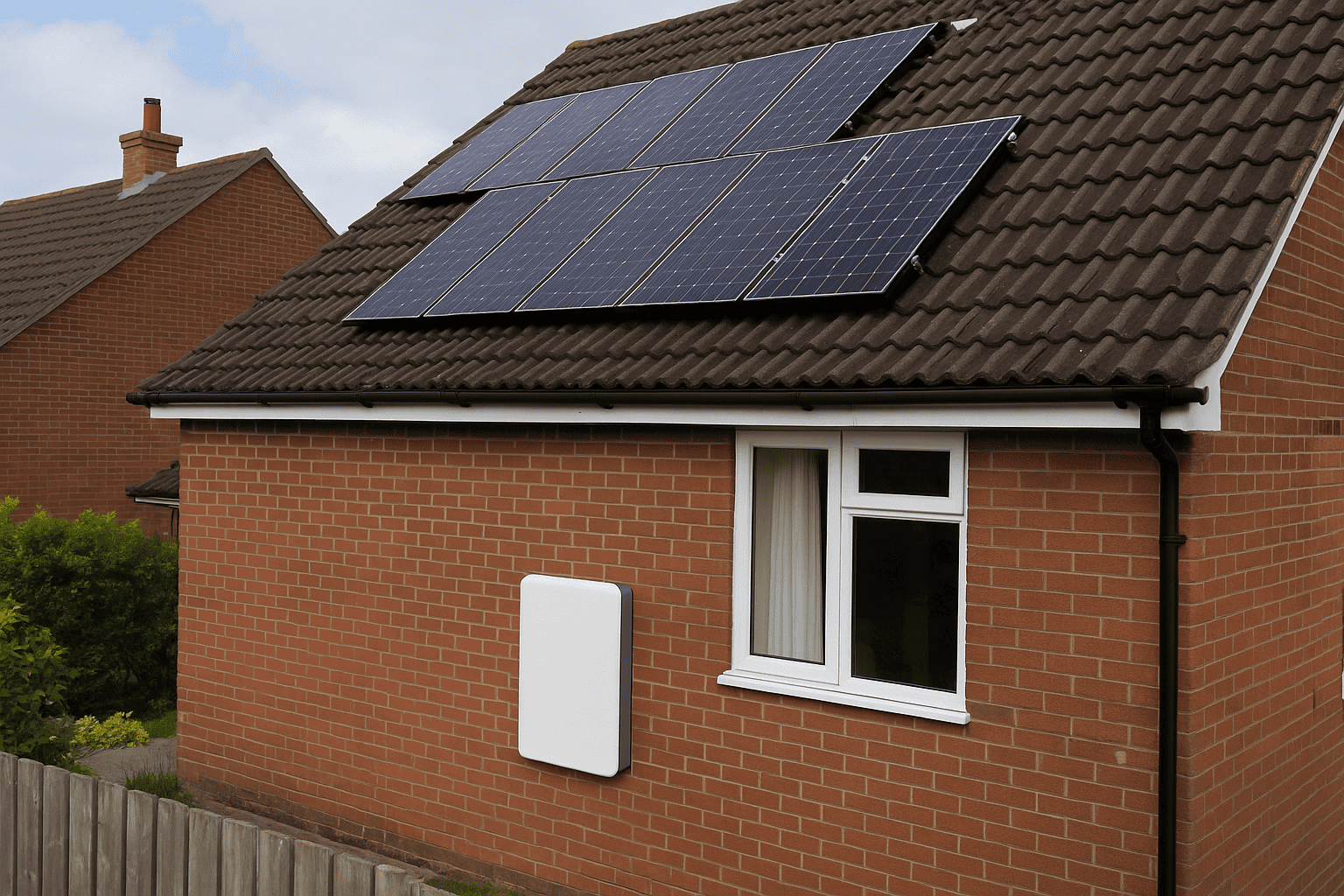

Low-carbon heat and power upgrades reduce that risk by pairing efficient electric heating with on-site generation and smarter consumption. An air-source heat pump typically delivers around 2.5–4.0 units of heat per unit of electricity, while a 4 kWp solar PV system often generates about 3,400 kWh per year in southern England (Energy Saving Trust). A home battery shifts surplus solar into evening demand, cutting grid imports.

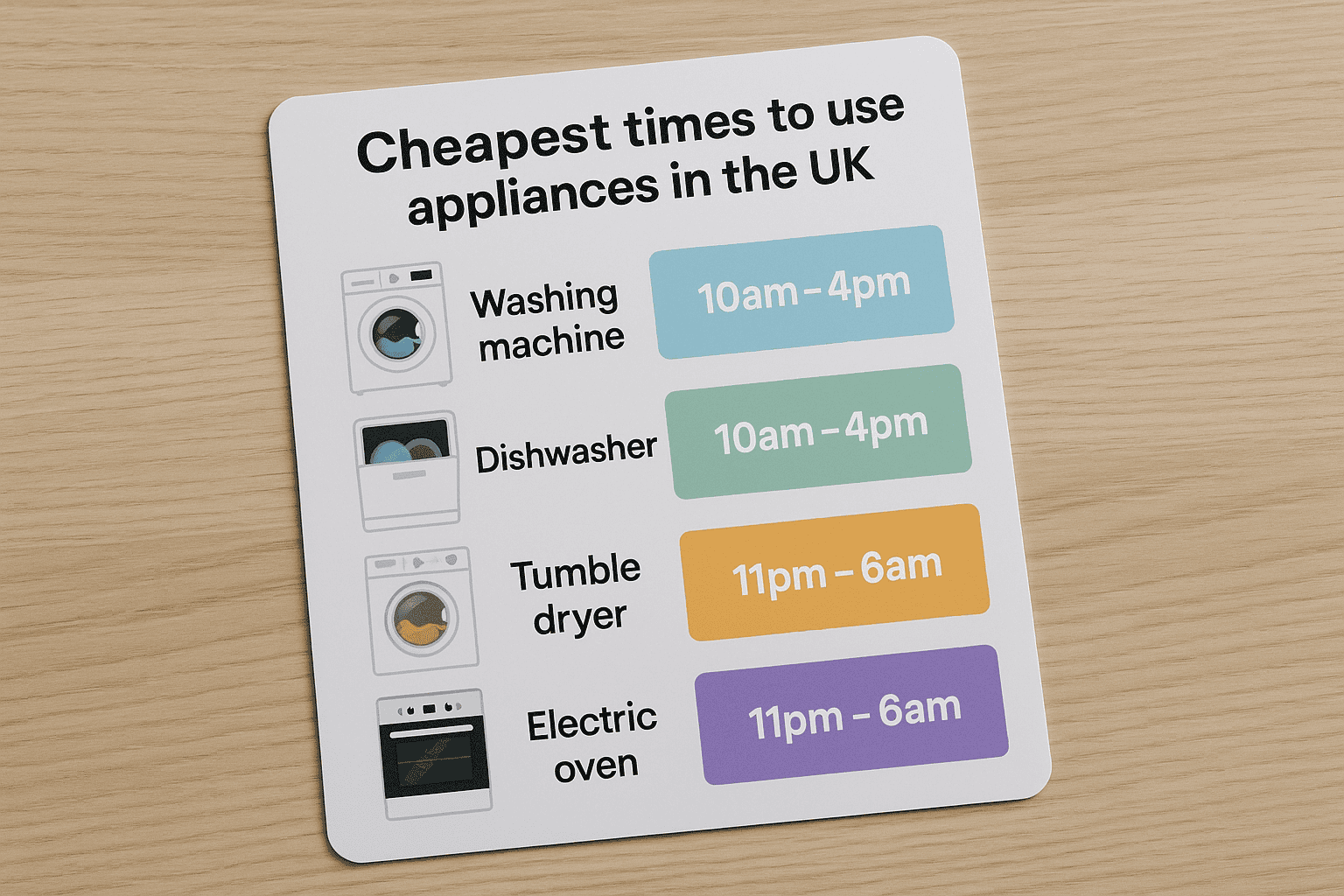

Size the heat pump to the property’s heat loss and upgrade radiators for lower flow temperatures (often 45–55°C). Match PV capacity to annual electricity demand, then choose a battery sized to daily surplus. Use a smart tariff with half-hourly pricing and schedule hot water, battery charging, and EV charging to cheaper periods (Ofgem).

These measures can cut gas use to zero, reduce exposure to price spikes, and improve EPC outcomes and comfort.

Costs, payback, and practical steps: budgeting, installer selection, grants, and retrofit planning

As of February 2026, the Boiler Upgrade Scheme offers a £7,500 grant towards an air-source heat pump in England and Wales. That single line item can shift the economics of a net-zero retrofit because installed costs commonly sit in the £10,000–£15,000 range for straightforward homes, before any radiator or cylinder upgrades. When grant funding covers 50–75% of the heat pump cost, payback depends less on capital outlay and more on heat demand, tariff choice, and system design.

Budgeting works best when homeowners separate “must-do” fabric repairs from carbon upgrades. A whole-house plan typically runs across 2–5 years, which spreads disruption and reduces the risk of stranded spend, such as fitting a larger heat pump before improving insulation. A practical starting point involves a room-by-room heat-loss assessment and a measured airtightness check; even a 10–20% reduction in heat demand can allow smaller emitters and lower flow temperatures, improving seasonal efficiency.

Installer selection should prioritise evidence over promises. For heat pumps, use an MCS-certified contractor and request a written design showing target flow temperature (often 35–45°C) and expected seasonal performance. For solar PV, confirm DNO notification and warranties; modern modules commonly carry 25-year performance guarantees, while inverters often sit nearer 10–12 years, which affects lifecycle budgeting.

Frequently Asked Questions

What defines a net-zero home in the UK, and how is net-zero calculated over a year?

A net-zero home in the UK balances annual greenhouse gas emissions from regulated energy use (space heating, hot water, lighting and fixed ventilation) with on-site or contracted renewable generation and verified offsets. Net-zero is calculated over 12 months by:

- Metering electricity and gas consumption in kWh.

- Converting energy to CO2e using UK grid and fuel factors.

- Subtracting exported renewable generation and certified offsets.

Which home energy efficiency measures deliver the largest carbon reductions per pound spent in UK properties?

In UK homes, loft insulation (to 270 mm) and cavity wall insulation usually deliver the largest carbon cuts per pound, often reducing space-heating demand by 10–25% at relatively low cost. Draught-proofing and heating controls (thermostatic radiator valves and smart programmers) also rank highly. LED lighting offers quick, low-cost savings, but smaller carbon impact.

What low-carbon heating options suit UK homes best, and how do heat pumps compare with hydrogen-ready boilers?

For most UK homes, air-source heat pumps suit best, delivering 3–4 units of heat per unit of electricity (COP 3–4) and cutting heating emissions by around 60–80% versus gas, depending on the grid. Ground-source heat pumps suit larger plots. Hydrogen-ready boilers fit existing radiators, but hydrogen for homes remains limited and less energy-efficient.

Which UK grants, schemes, and VAT reductions can homeowners use to fund net-zero upgrades in 2026?

In 2026, homeowners can fund net-zero upgrades through the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (£7,500 towards an air-source heat pump), the Energy Company Obligation (ECO4) for insulation and heating (mainly for low-income or vulnerable households), and 0% VAT on energy-saving materials (extended to 31 March 2027). Some councils also offer local retrofit grants and loans.

How can homeowners verify a property’s net-zero performance using EPC ratings, SAP scores, and energy monitoring data?

Check the EPC for an A rating and low annual CO₂ (often 0–1 tCO₂/year). Review the SAP score: net-zero-ready homes typically score 90–100+. Confirm with 12 months of monitoring: compare metered electricity and any gas to PV generation and export; net-zero shows annual net import near 0 kWh.